TL;DR

Fuzz over the host header to leverage reverse proxies misconfigurations. Identify the administration IP instance and use replace your Host header with it to delete the carlos user. This is considered a SSRF because the one sending the wrong request is not the Webserver but the reverse proxy.

Learning Material

It is sometimes also possible to use the Host header to launch high-impact, routing-based SSRF attacks. These are sometimes known as “Host header SSRF attacks”, and were explored in depth by PortSwigger Research in Cracking the lens: targeting HTTP’s hidden attack-surface.

Classic SSRF vulnerabilities are usually based on XXE or exploitable business logic that sends HTTP requests to a URL derived from user-controllable input. Routing-based SSRF, on the other hand, relies on exploiting the intermediary components that are prevalent in many cloud-based architectures. This includes in-house load balancers and reverse proxies.

Although these components are deployed for different purposes, fundamentally, they receive requests and forward them to the appropriate back-end. If they are insecurely configured to forward requests based on an unvalidated Host header, they can be manipulated into misrouting requests to an arbitrary system of the attacker’s choice.

These systems make fantastic targets. They sit in a privileged network position that allows them to receive requests directly from the public web, while also having access to much, if not all, of the internal network. This makes the Host header a powerful vector for SSRF attacks, potentially transforming a simple load balancer into a gateway to the entire internal network.

You can use Burp Collaborator to help identify these vulnerabilities. If you supply the domain of your Collaborator server in the Host header, and subsequently receive a DNS lookup from the target server or another in-path system, this indicates that you may be able to route requests to arbitrary domains.

Having confirmed that you can successfully manipulate an intermediary system to route your requests to an arbitrary public server, the next step is to see if you can exploit this behavior to access internal-only systems. To do this, you’ll need to identify private IP addresses that are in use on the target’s internal network. In addition to any IP addresses that are leaked by the application, you can also scan hostnames belonging to the company to see if any resolve to a private IP address. If all else fails, you can still identify valid IP addresses by simply brute-forcing standard private IP ranges, such as 192.168.0.0/16.

CIDR notation

IP address ranges are commonly expressed using CIDR notation, for example, 192.168.0.0/16.

IPv4 addresses consist of four 8-bit decimal values known as “octets”, each separated by a dot. The value of each octet can range from 0 to 255, meaning that the lowest possible IPv4 address would be 0.0.0.0 and the highest 255.255.255.255.

NOTE

In CIDR notation, the lowest IP address in the range is written explicitly, followed by another number that indicates how many bits from the start of the given address are fixed for the entire range. For example,

10.0.0.0/8indicates that the first 8 bits are fixed (the first octet). In other words, this range includes all IP addresses from10.0.0.0to10.255.255.255.

Lab

This lab is vulnerable to routing-based SSRF via the Host header. You can exploit this to access an insecure intranet admin panel located on an internal IP address.

To solve the lab, access the internal admin panel located in the 192.168.0.0/24 range, then delete the user carlos.

NOTE

To prevent the Academy platform being used to attack third parties, our firewall blocks interactions between the labs and arbitrary external systems. To solve the lab, you must use Burp Collaborator’s default public server.

Write-up

The whole point of this lab is understanding how can reverse-proxies and everything involved before reaching our target can be tested. In this case, if we try to reach the WebApp by specifying an other Host value, the intermediate resources might use it to send the request to the wrong host.

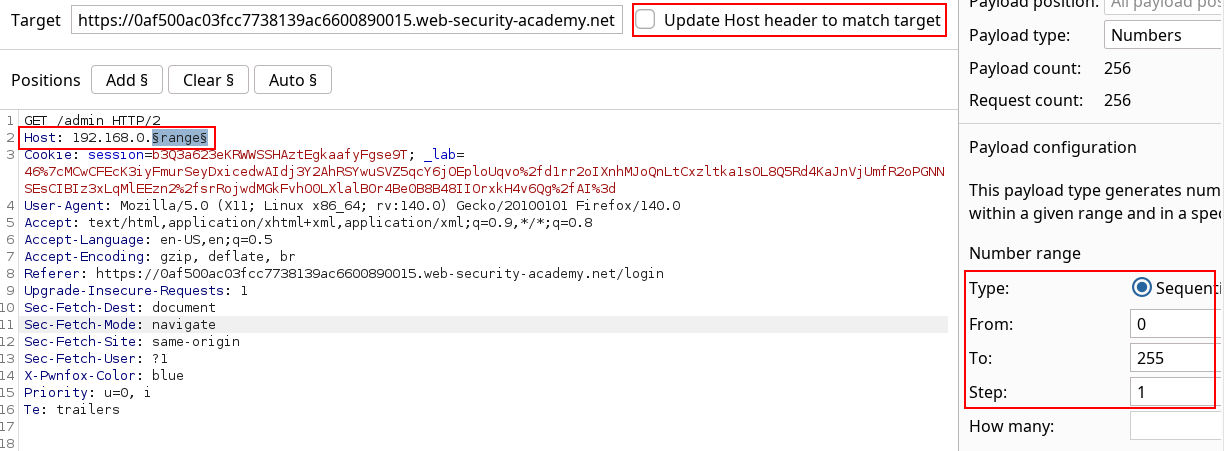

The lab context tells us to fuzz over the Host header against the internal admin panel, which is usually /admin, over the local IP range so there we go.

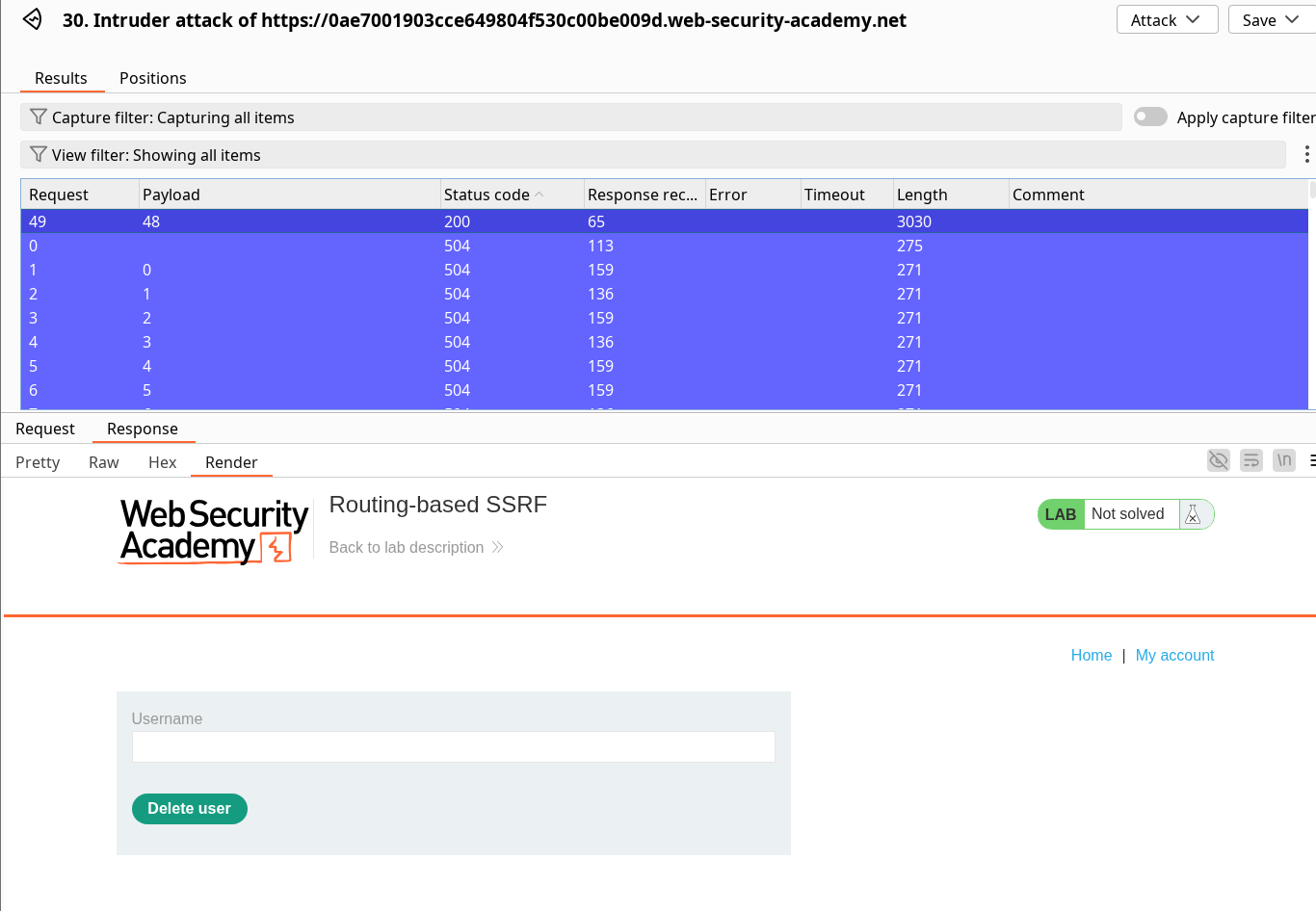

The results of the fuzz gets us a successful admin panel.

I have tried to directly replay the sacred POST /admin/delete?username=carlos though I ended up on a 400 error indicating missing csrf parameter, (thanks the lab to be so verbose). Because of this, I had to replicate the flow of execution by replaying the GET request, intercepting the deletion POST request and modify again the Host header.

Once you have successfully sent the deletion request, this will solve the lab.